About Us

From St. Luke the Evangelist, to Absalom Jones, to Bishop Michael Curry, we are surrounded by those who came before and forged a path of religious freedom, educational and economic equity, and social justice activism. We strive to embody our legacy as a part of the Black Church within the Episcopalian tradition.

Therefore, since we are surrounded by such great cloud of witnesses, let us throw off everything that hinders… And let us run with perseverence the race marked out for us.

Hebrews 12:1 NIV

In the African religious tradition, we respect those who have come before. We purposefully take time on their feast day to honor them and draw inspiration from a life well-lived.

Absalom Jones

Absalom Jones was born into slavery in Sussex County, Delaware, on November 7, 1746. When he was sixteen, his owner sold him along with his mother and siblings to a neighboring farmer. That year the farmer kept Absalom, but sold his mother and siblings, and moved to Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, where he became a merchant.

By 1778 Absalom had purchased his wife’s freedom so that their children would be free; he asked for aid by donations and loans. In 1784, Absalom gained manumission from his owner—who was possibly inspired by revolutionary ideals. Absalom took the surname “Jones” as an indication of his American identity.

Disappointed at the racial discrimination he experienced in a local Methodist Episcopal church, he founded the Free African Society with Richard Allen in 1787, a non-denominational mutual aid society to help newly freed slaves in Philadelphia. As 1791 began, Jones started holding religious services at FAS, which the following year became the core of his African Church in Philadelphia. Jones wanted to establish a black congregation independent of white control, while remaining part of the Episcopal Church. After a successful petition, the African Episcopal Church of St. Thomas, the first black church in Philadelphia, opened its doors on July 17, 1794. Jones and Allen later separated, as their religious lives took different directions. They remained lifelong friends and collaborators.

Jones was ordained as a deacon in 1795 and as a priest in 1802, became the first African-American priest in the Episcopal Church of the United States. He is listed on the Episcopal calendar of saints. He is remembered liturgically on the date of his death, February 13, in the 1979 Book of Common Prayer as “Absalom Jones, Priest, 1818”.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Jones, Absalom, A Narrative of the Proceedings of the Black People, During the Late Awful Calamity in Philadelphia, in the Year 1793: And a Reputation of some Censures, Thrown upon Them in Some Late Publications (Philadelphia: Printed for the authors by W. W. Woodward, 1794), also by Richard Allen

Jones, Absalom and Richard Allen, The life, experience, and Gospel labors of the Rt. Rev. Richard Allen: to which is annexed, the rise and progress of the African Methodist Episcopal Church in the United States of America: containing a narrative of the yellow fever in the year of our Lord 1793: with an address to the people of color in the United States. (Philadelphia : F. Ford and M.A. Riply, 1880)

Jones, Absalom, 1746-1818: A Thanksgiving sermon, preached January 1, 1808, in St. Thomas’s (or the African Episcopal) Church, Philadelphia, on account of the abolition of the African slave trade, on that day, by the Congress of the United States. ([Philadelphia, Rhistoric Publications, 1969])

Alexander Crummell

Alexander Crummell was born on March 3, 1819 in New York City to Charity Hicks, a free woman of color, and Boston Crummell, a former slave. Both of Crummell’s parents were active abolitionists, and their home was used to publish the first African-American newspaper, Freedom’s Journal. was a pioneering African-American minister, academic, and African nationalist.

From 1849 to 1853, Crummell studied at Queens’ College, Cambridge, sponsored by Benjamin Brodie, William Wilberforce, Arthur Penrhyn Stanley, James Anthony Froude, and Thomas Babington Macaulay. Crummell became the first officially black student recorded as graduated in the university records. Ordained as an Episcopal priest in the United States, Crummell went to England in the late 1840s to raise money for his church by lecturing about American slavery. Abolitionists supported his three years of study at Cambridge University, where Crummell developed concepts of pan-Africanism. After returning to the United States in 1872 from Liberia where he’d lived and worked for 20 years, Crummell was called to St. Mary’s Episcopal Mission in Washington, DC.

In 1875, he and his congregation founded St. Luke’s Episcopal Church, the first independent black Episcopal church in the city. They built a new church on 15th Street, NW, beginning in 1876, and celebrated their first Thanksgiving there in 1879. Crummell served as rector at St. Luke’s until his retirement in 1894. He then taught at Howard University from 1895 to 1897.

Despite frustrations, Crummell never stopped working for the racial solidarity he had advocated for so long. Throughout his life, Crummell worked for black nationalism, self-help, and separate economic development. He spent the last years of his life founding the American Negro Academy, the first organization to support African-American scholars, which opened in 1897 in Washington, DC. Alexander Crummell died in Red Bank, New Jersey, on September 10, 1898.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

[1840] 1979, “New York State Convention of Negroes, 1840,” in A Documentary History of the Negro People in the United States, volume 1: From the Colonial Times through the Civil War, edited by H. Aptheker. New York: Citadel, 198–205.

1862, The Future of Africa: Being Addresses, Sermons, etc., etc., Delivered in the Republic of Liberia, second edition, New York: Charles Scribner.

1882, The Greatness of Christ, and Other Sermons, New York: Thomas Whittaker.

1891, Africa and America: Addresses and Discourses, Springfield, Mass.: Willey & Co.

1992, Destiny and Race: Selected Writings, 1840–1898, edited by W. J. Moses, Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press.

1995, Civilization & Black Progress: Selected Writings of Alexander Crummell on the South, edited by J. R. Oldfield, Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia.

Pauli Murray

Murray decided to pursue her career goal of working as a civil rights lawyer and enrolled in the law school at Howard University in 1941, where she also became aware of sexism. She called it “Jane Crow”, alluding to the Jim Crow laws that enforced racial segregation in the Southern United States. Murray graduated first in her class in 1944, but she was denied the chance to do post-graduate work at Harvard University because of her gender. Traditionally, men who were graduated first in the class were awarded Julius Rosenwald Fellowships for graduate work at Harvard University, but that university did not accept women. Murray was rejected despite a letter of support from President Franklin D. Roosevelt. She wrote in response, “I would gladly change my sex to meet your requirements, but since the way to such change has not been revealed to me, I have no recourse but to appeal to you to change your minds. Are you to tell me that one is as difficult as the other?”

She earned a master’s degree in law at University of California, Berkeley. After passing the California bar exam in 1945, Murray was hired as the state’s first black deputy attorney general in January of the following year. That year, the National Council of Negro Women named her its “Woman of the Year” and Mademoiselle magazine did the same in 1947. Thurgood Marshall, National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) Chief Counsel, called Murray’s 1950 book, States’ Laws on Race and Color, the “bible” of the civil rights movement. John F. Kennedy appointed Murray to serve on the 1961–1963 Presidential Commission on the Status of Women. Murray became the first African-American to receive a Doctor of Juridical Science degree from Yale Law School in 1965, and 1966, she co-founded the National Organization for Women. Ruth Bader Ginsburg named Murray as co-author of a brief on the 1971 case Reed v. Reed, in recognition of her pioneering work on gender discrimination.

In 1973, Murray left academia to focus on her work with the Episcopal Church. Drawn to the ministry, she began her studies at General Theological Seminary and was ordained at the National Cathedral in 1977—in the first year that any women were ordained by that church. She served at Church of the Atonement in Washington D.C. from 1979 to 1981 and at Holy Nativity Church in Baltimore until her death in 1985. On July 1, 1985, Pauli Murray died of pancreatic cancer in the house she owned with lifelong friend, Maida Springer Kemp, in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Books

Dark Testament and Other Poems. New York, NY: W.W. norton & Company, 2018.

Proud Shoes: The Story of an American Family. New York: Harper & Row, 1956. (Reprinted in 1978, paperback by Beacon Press, 1999)

Song in a Weary Throat: An American Pilgrimage. New York: Harper & Row, 1987. (Reissued in 2018 with a new introduction by Liveright Publishing, a division of W.W. Norton & Company)

States’ Laws on Race and Color. Cincinnati: Women’s Division of Christian Service, Board of Missions and Church Extension. Methodist Church, 1951.

The Constitution and Government of Ghana. London: Sweet and Maxwell, 1964. Murray, Pauli, and Leslie Rubin.

Articles

- “An American Credo.” Common Ground 5, no. 2 (1945): 22-24.

- “And the Riots Came.” The Call, Friday, August 13 1943, 1; 4.

- “A Blueprint for First Class Citizenship.” The Crisis 51 (1944): 358-59.

- “Negro Youth’s Dilemma.” Threshold, April 1942, 8-11.

- “Negroes Are Fed Up.” Common Sense, August 1943, 274-76.

- “The Right to Equal Opportunity in Employment.” California Law Review 33 (1945): 388-433.

- “Roots of the Racial Crisis: Prologue to Policy.” J.S.D., Yale University, 1965

- “Three Thousand Miles on a Dime in Ten Days.” In Negro Anthology: 1931-1934, edited by Nancy Cunard, 90-93. London: Wishart and Co., 1934.

- “Why Negro Girls Stay Single.” Negro Digest 5, no. 9 (1947): 4-8.

- “An Alternative Weapon.” South Today, (Winter 1942-1943): 53-57. Murray, Pauli, and Henry Babcock.

- “Jane Crow and the Law: Sex Discrimination and Title Vii.” George Washington Law Review 34, no. 2 (1965): 232-56. Murray, Pauli, and Mary O. Eastwood.

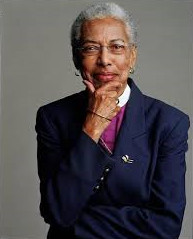

Barbara C. Harris

Prior to her ordination to the priesthood, Harris served as head of public relations for the Sun Oil Company. Throughout her various careers, Harris was noted for her liberal views and her outspokenness. As early as 1989 she was reported as arguing for gay rights and lambasting the Episcopal Church for racism and sexism.

Post retirement, Harris felt called to the ministry, and in 1979, was ordained as a deacon; then as a priest in 1980. Harris was the priest-in-charge of St. Augustine of Hippo Church in Norristown, Pennsylvania, from 1980 to 1984. She also served as chaplain to the Philadelphia County prisons, and as counsel to industrial corporations for public policy issues and social concerns. She was named executive director of the Episcopal Church Publishing Company in 1984, and publisher of The Witness magazine. In 1988 she served as interim rector of the Church of the Advocate in Philadelphia which was her home church.

Harris was elected bishop suffragan of the Episcopal Diocese of Massachusetts, on September 24, 1988, at a special convention of diocesan delegates. Her election was controversial, in part because she was divorced and had not attended seminary. She was also the first woman to be elected to the position of bishop not only in the Episcopal Church, but in all of the Anglican Communion. Some members of the church felt it was inappropriate to elevate a woman to the position of bishop, and others were concerned that her election would strain relations with the wider Anglican Communion. As the first woman ordained as a bishop, and as an African American, she received death threats and obscene messages. Though urged to wear a bulletproof vest to her ordination, she refused. A contingent of the Boston police were assigned to her consecration. Her comment was merely, “I don’t take this in a personal way.”

Speaking of her work as bishop, Harris said, “I certainly don’t want to be one of the boys. I want to offer my peculiar gifts as a black woman … a sensitivity and an awareness that comes out of more than a passing acquaintance with oppression.”

Harris served for 13 years as bishop in the Episcopal Diocese of Massachusetts and retired in 2003. She then assisted the bishop in the Episcopal Diocese of Washington, DC, until 2007. She was also the president of the Episcopal Church Publishing Company, publishers of The Witness magazine. Harris died in Lincoln, Massachusetts, on March 13, 2020, at age 89.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Parting Words: A Farewell Discourse (Cloister Books). Harris, Barbara C. (Cowley Publications)

Beyond Powershift: Theological Questions in a Changing World and The God of Philosophers (The Westminster Tanner-McMurrin Lectures on the History and Philosophy of Religion at Westminster College IV & V, 1992 & 1993). Harris, Barbara C. and McInerny, Ralph. Westminster College, 1993.

Hallelujah, Anyhow!: A Memoir.Harris, Barbara C. (Church Publishing Inc, United States, 2018)

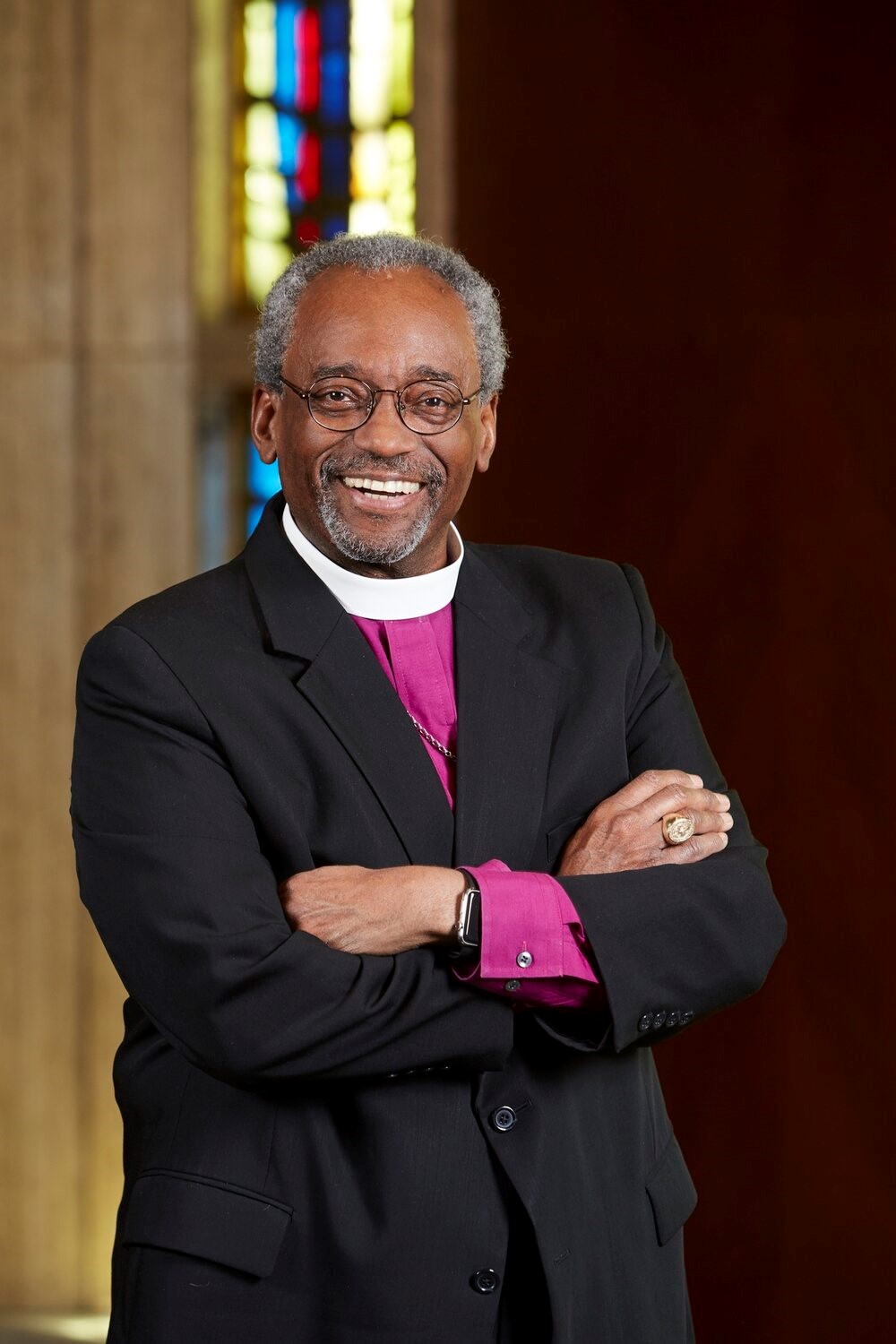

He graduated with high honors from Hobart College in Geneva, New York, in 1975. He then earned a Master of Divinity degree, in 1978, from the Yale Divinity School, in association with Berkeley Divinity School. Curry has also studied at The College of Preachers, Princeton Theological Seminary, Wake Forest University, the Ecumenical Institute at St. Mary’s Seminary in Baltimore, and the Institute of Islamic, Christian, and Jewish Studies.

In his parish ministries, Curry participated in crisis response pastoral care, the founding of ecumenical summer day camps for children, preaching missions, creation of networks of family day care providers, and the brokering of investment in inner city neighborhoods. He inspired a $2.5 million restoration of the St. James’ church building after a fire.

When he was consecrated at Duke Chapel in Durham on June 17, 2000, as the eleventh bishop of the Episcopal Diocese of North Carolina, he became the first African-American diocesan bishop of the Episcopal Church in the American South. Nearly 40 bishops participated in the service, including Robert Hodges Johnson, J. Gary Gloster, and Barbara C. Harris as consecrators.

In 2015, Curry became one of four candidates nominated for the election of the presiding bishop. On 27 June, he was elected by the House of Bishops meeting in St. Mark’s Cathedral in Salt Lake City on the first ballot with 121 of 174 votes cast. Laity and clergy in the House of Deputies ratified Curry’s election later the same day. Curry was installed as presiding bishop and primate on November 1, 2015, All Saints’ Day, during a Eucharist at Washington National Cathedral.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Crazy Christians: A Call to Follow Jesus. Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: Morehouse Publishing. 2013.

Songs My Grandma Sang. Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: Morehouse Publishing. 2015.

Following the Way of Jesus. Church’s Teachings for a Changing World, Volume 6. New York, NY: Church Publishing. 2017.

The Power of Love: Sermons, Reflections, and Wisdom to Uplift and Inspire. New York, NY: Avery / Random House. 2018.

Love is the Way: Holding on to Hope in Troubling Times. New York, NY: Avery. 2020.